Great Danes and other large dogs naturally have large and extra large stomachs. They also tend to have extra large appetites for food, and unless their owners prevent it, tend to gulp down their meals and cap it off with a big serving of water. If such an overstuffed animal should then decide to take a vigorous romp outdoors, it could find itself suddenly in the throes of gastric bloat and torsion, a dire digestive system condition that is among the most common of all canine disorders requiring emergency care.

Also known as gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV) the clinical signs of this condition are usually unmistakable, and immediate treatment is needed in order to save a stricken animals life. An estimated 25 to 40 percent of GDV victims die for lack of emergency care within 6 to 12 hours following it’s onset. In addition to Great Danes, Akita’s, German Shepherds, Greyhounds, Saint Bernards, Labrador Retrievers and Irish Wolfhounds are among the breeds most diagnosed with GDV. Although smaller animals that have elongated abdomens-such as Dachshunds and Basset Hounds are also at an elevated risk for this lethal disorder, 90 percent or more of those afflicted are large dogs.

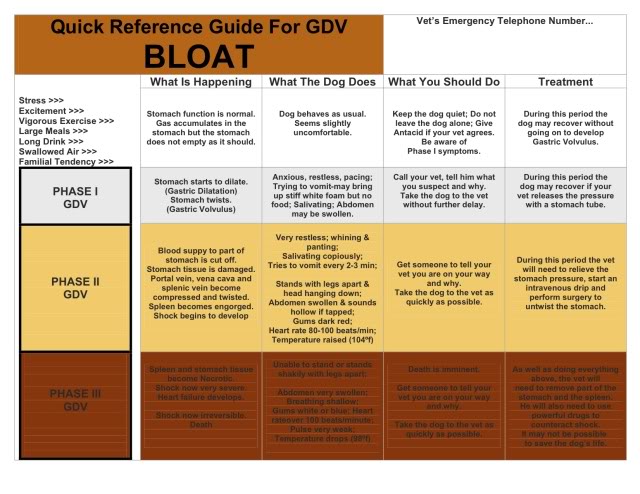

Gastric Bloat is a severe expansion (dilatation) of the stomach, typically after a large meal that is followed by the eager consumption of water and a period of strenuous exercise. The inflation of the stomach is caused by a combination of food, liquid and air intake that, when blended with normal digestive secretions , yields an intolerably high amount of gas and abdominal pressure. Torsion occurs when the distended stomach twists upon itself. If it twists more than 180 degrees on it’s long axis, the condition is called volvulus.

Normally the buildup of gas would be relieved by burping or vomiting undigested food. But when the stomach twists, it closes off the sphincters that control the passage of ingested matter from the esophagus to the stomach and from the stomach to the small intestine. Consequently, despite the dogs futile attempts to belch, vomit or defecate, the stomach becomes increasingly distended with gas.

As the gas accumulates, it puts great pressure on the walls of the stomach. The stomach becomes taut, like a basketball, and it’s wall is stretched very thin. With the stomach distended and twisted, the blood supply to the stomach wall is severely compromised, resulting in tissue death, and unless treated promptly, the release of toxins. Bacteria can then proliferate in the stomach wall and pass into the animals bloodstream. Additionally, the distended stomach blocks the blood flow from the abdomen to the heart, and this, combined with the formation of blood clots in the stomach, can cause the dog to go into shock.

If the oxygen supply to the stomach is not restored quickly and the bloating continues, the stomach wall will deteriorate rapidly and may rupture. Within a short period, usually a few hours or so, the suffering dog may die from a combination of factors: tissue damage, a ruptured stomach, kidney failure, respiratory insufficiency, cardiac failure and shock.

Signs of GVD

Signs of GVD

The earliest signs of GVD are general anxiety, restlessness, pacing and whimpering. Initially, the animal will show no interest in water or food. On the contrary, it may begin drooling heavily, retching and trying to vomit without success.

Within a half hour or so, as the unproductive retching continues, the animals abdomen will become visibly swollen. The dog will begin to breathe rapidly and pant in distress. Tapping on it’s abdomen will produce a hollow, drum like sound. The dog will lie down, possibly in a curled up position, and will not respond to attempts to get it back on it’s feet. The animals gum tissue and other mucous membranes may become pale, and it’s heart will beat rapidly. At this point, serious bloating will have occurred and a true emergency exists.

Once the attack begins, the dogs condition will deteriorate very rapidly and there is really nothing that the owner can do except get the animal to the nearest veterinarian immediately.

Emergency Treatment:

Emergency Treatment:

The veterinarian will first begin to treat the dog for shock, by giving it fluids intravenously. Then a tube about the diameter of a garden hose, will be inserted into the animals mouth and gently fed into it’s stomach. The idea is to draw the gas out of the stomach through this tube and if the stomach is not twisted, that will usually work. They will also put fluid down the tube to lubricate food and other material that’s in the stomach and try to draw that out too.

In some instances, a stomach that has already begun to twist may de-rotate on it’s own once excess gas has been released through a tube or suctioned out with a needle. But what usually happens is that decompression of the stomach is only temporary because the dog will inhale more air, which will mix with the fermenting material in their stomach. More gas will then form, and the torsion will not be relieved. So, in most cases, once the stomach twists, surgery is needed to untwist it.

An x-ray may be taken to confirm the gastric torsion, but a veterinarian may not want to waste valuable time when the condition is clearly apparent. The dog will then be anesthetized, and the surgeon will open the abdomen, decompress the stomach, and then untwist it by hand to it’s normal position. If it looks healthy-wonderful! But if it’s been twisted for a long period of time, portions of the stomach tissue may have died, and any dead sections must be removed. After that, they need to make sure that the stomach can never twist again. So they will perform an gastroplexy-a procedure in which they suture part of the stomach to the abdominal wall so that if the stomach bloats again, which is not unlikely, it will be prevented from twisting.

The surgery is risky, because it is an emergency procedure done on a severely compromised patient. In dogs with dead stomach tissue, the mortality rate is about 70%. but even for animals with healthy stomach tissue, the mortality rate is about 30%. On a brighter note, animals that survive an attack of GDV and the ensuing gastroplexy can go home after a few days, and with proper postoperative rest, can be back to normal in a few weeks.

The risk of gastric bloat can be greatly reduced by feeding two to three small meals a day to a large dog, rather than one large meal. Dogs in general should not be allowed to consume large amounts of water or engage in strenuous exercise for at least 2 hours following a meal.

Dogwatch